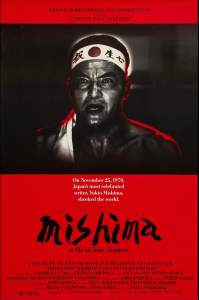

This week, after a whirlwind tour of some recent big screen releases, Jeff Godsil revisits Paul Schrader's Mishima: A Life in Four Parts, from 1985, and Matthew of KBOO's bedtime story program Gremlin Time looks at the 1949 Ealing comedy, A Run for your Money, while in the book nook, we scrutinize the new BFI Film Classic on Sofia Coppola's Lost in Translation. Does it answer the question of what Bill Murray whispers?

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

BFI Lost in Translation Quotes

Sophia Coppola is 51 and has made about eight feature films and numerous shorts and music videos, but already there are seven books about her work. Here comes an eighth. This is the latest addition in the British film Institute's film classics series about lost in translation written by Suzanne Ferriss, who has already written a full length study of Sophia Coppola's filmography, The Cinema of Sofia Coppola, which we reviewed here a few months ago, and is also editor of the recent 500 page anthology The Bloomsbury Handbook to Sofia Coppola. Suzanne Ferriss is Professor Emeritus at Nova Southeastern University, and has written previous books on fashion and motorcycles.

This time, professor Ferriss focuses on one film, and in the most satisfying manner. The book is divided into six chapters, along with an introduction, and follows the conceit of each chapter being an itinerary item for a trip to a foreign land.

The intro focuses on the very beginning and the very end of the film, and how these moments manipulate genre expectations.

Chapter 1, Trip Planning, offers a detailed production history including financing deals and marketing strategies. Coppola is something of a nepo-baby, which some seem to find blight on the entertainment industry, but if she is one, the status provides her with access to good young talent.

Chapter 2, Arrivals discusses why the film opens with a shot of Scarlett Johansson’s bottom, and the source of that imagery (a painter painter named John Kacere), and discusses the short story that was the original version of Lost in Translation. There is also a great deal of discussion of Coppola’s style of framing her performers. We also come away with the realization that the director is deeply immersed in art history and music culture.

Chapter3, Accommodations, explores how Coppola uses space and rooms to explore the psychology of her characters. It’s worth noting that Coppola’s group scenes are blocked like real life, not like TV show blocking, or a sit-com, where performers make pointless movement around each other to provide minimal visual interest. Here, they stand still or drift about in the manner of real people.

As the author writes in the introduction, “The film’s guerrilla-style handheld photography underscores the impression of cinéma vérité and stresses movement, yet much of the film employs static images, blurring the boundaries between moving image and still photography. It also mixes tones, alternating between light humour and deep insight into human connection. Broad comedy is balanced by moments of quiet reflection. As the opening and closing scenes show, the film often eschews dialogue in favour of image, performance and music. Yet rarely do popular music lyrics crudely substitute for dialogue. The film’s soundtrack consists instead of ambient sounds linked to location or electronic-based instrumentals designed to convey cultural and emotional detachment.”

Chapter 4, Sights, contrasts Bill Murray’s experience of interiors such as photo studios, and TV studio sets, in contrast with Scarlett Johansson’s exploration of Japan’s sights and landscapes.

Chapter 5, Departures, examine in detail the film’s ending sequence, how it is framed and posed, why Bill Murray walks backwards back to his taxi, and other nuances that deviate from some of the film’s influences, such as Brief Encounter, Before Sunrise, and In the Mood for Love. The author also hints that clues to the unheard words that Murray whispers can be found in the songs playing through the rest of the movie.

Before an extensive notes section, Chapter 6 analyses the film’s reception in what becomes a mini-anthology of mainstream media reviews, and goes on to compare Lost in Translation with Coppola’s subsequent films.

As the author notes, Lost in Translation “evocatively represents the bifurcated nature of travel as an amalgam of stasis and motion.”

And she writes of the style of the film thus:

‘While their flexible, mobile style would have suited digital video (and their low budget), the director insisted on using film, with stock of a higher than usual speed to accommodate natural light.

“Together, these choices stress authenticity – and are key to the film’s lasting impression in audiences’ imaginations. The performances appear as the natural, unscripted encounters of strangers in a foreign locale. The cinematography retains the realism of lighting and motion – the vibrancy of urban existence in Tokyo, the serenity of cloistered temples in Kyoto, the fleeting stasis and spaces of withdrawal provided by the hotel.

"The elevator and other spaces in the Park Hyatt Tokyo shape our understanding of the characters and configure their relationships. As in her later film Somewhere (2010), the hotel is crucial to the film’s narrative, audiovisual design and meaning.“

The book Lost in Translation packs a lot of information and ideas into it’s almost 120 pages, and currently stands as the definitive account of this great film from 2003.